“Effectiveness of Mental Health Advocacy on Twitter During Mental Health Month” by B. Antonia Delawie

Magnificat, April 2022

Abstract

Scholarship on the role of social media in mental health advocacy generally agrees that social media plays a big role in mental health advocacy these days. But scholars have yet to extensively explore how effective mental health advocacy on social media really is. This essay addresses this gap in the literature by looking at the correlation between Twitter data and Google searches related to mental health. I demonstrate that there isn’t a significant correlation because there was a slight increase in word usage on Twitter, but Google search data didn’t show any significant increase in the month of May that could have been caused by the Twitter advocacy.

Introduction

Scholars have speculated about the role of social media in mental health advocacy ever since the first emergence of the phenomenon. Social media can seem like a powerful advocacy tool since it gives a voice to the everyday person to get their thoughts out to millions of people. Tweets go viral every single day, but the real question is not about how many people a tweet reaches, but how seeing that tweet affects their behavior. My research aims to provide some insight into this question by looking at the correlation between the frequency of Twitter word usage and the frequency of Google searches related to mental health in Mental Health Awareness Month compared to the rest of the year. This correlation isn’t a certain indicator of people’s behaviors, but it could lend us some interesting insight into the question.

Research questions and Thesis statement

My main research question focuses on the effectiveness of mental health advocacy during Mental Health Awareness month.

- RQ1: How effective is Twitter advocacy at raising awareness during Mental Health Awareness month?

My other research questions help me further develop how I will be able to get an answer to my main research question.

- RQ2: How much more are people using mental health/ mental health advocacy related words on Twitter during mental health month?

- RQ3: How much more are people searching for mental health related words/ terms on Google (e.g. ‘therapist near me’)?

- RQ4: What is the correlation between these two things?

- RQ5: What are these two data points telling us?

- RQ6: What is the significance of Twitter in mental health advocacy?

- RQ7: What are the limitations of this method?

- RQ8: What factors could have an effect on the results?

My thesis statement is that the correlation between Twitter word usage and Google searches related to mental health could indicate the effectiveness of social media advocacy on affecting people’s actual behaviors.

Method

I have requested and was granted access to Twitter Application Programming Interface (API) for academic research purposes. Unfortunately, this version of the program did not provide full access to all of the Twitter data that I needed so I needed to slightly modify my search words. I used Twitter API with the help of Python programming language to get data about the frequency of the use of mental health related words/phrases in Mental Health Awareness Month (May) compared to the rest of the year.

My original mental health related words/phrases were: mental health, mental illness, mental health awareness month, anxiety, depression, bipolar, schizophrenia and dementia. I chose these specific mental health disorders because they are the five most common ones (DuBois-Maahs, 2018). But because of the limitations of my access to Twitter API I needed to shorten this list to just two words. The two phrases I chose are ‘mental health’ and ‘anxiety’, since they seemed like the most relevant ones.

After this I used Google Trends (trends.google. com) to get data about the frequency of searches for words/phrases related to mental health seeking behaviors in Mental Health Awareness Month (May) compared to the rest of the year. My words/phrases related to mental health seeking behaviors are:

- Therapist near me

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Bipolar Disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Dementia

- Do I have anxiety?

- Do I have depression?

- Do I have bipolar disorder?

- Do I have schizophrenia?

- Do I have dementia?

I chose to continue with my original set of words for this search instead of narrowing down this search too to get more accurate results.

Originally, I was going to look at both of these datasets between January 1st, 2014 and December 31st, 2019. The plan was to use the span of five years, so that the events of a particular year will be less likely to affect the results I get. The year of 2020 was also going to be excluded from my dataset because the unprecedented world-wide pandemic had an effect on people’s mental health that is different from just a usual year, so including it would interfere with the results too much. But I had to change this method too because of the limitations of my API access.

I choose to look at only the year of 2019 and instead of looking at the full dataset, I will be looking at the frequency of the word usage on Twitter based on specific intervals of time within each month. I needed to find a date that doesn’t have any holiday that affects people’s social media usage in any of the months (e.g. people use social media less during Christmas since they are spending time with their families). I chose the first Friday of every month, which is:

- January 4th, 2019

- February 1st, 2019

- March 1st, 2019

- April 5th, 2019

- May 3rd, 2019

- June 7th, 2019

- July 5th, 2019

- August 2nd, 2019

- September 6th, 2019

- October 4th, 2019

- November 1st, 2019

- December 6th 2019

None of these days are national holidays. I looked at this same dataset on Google.

After I had all of this data I analyzed them and determined if the dataset has any outlying areas unrelated to my research questions that I have to correct for. After that I compared the two datasets to determine how effective mental health advocacy in the month of May is at getting people to start looking into their mental health and getting help for it compared to the rest of the year based on the correlation between these two datasets.

After this, based on the results, I applied the theories of Lazarsfeld’s Two-Step-Hypothesis, Baudrillard’s theory of Simulation and the Effects Tradition to my findings to theorize why the results are what they are.

Lazarsfeld’s Two-Step-Hypothesis was first proposed by Paul Lazarsfeld in 1940 in Elmira, New York (Littlejohn, 2017). It says that people are affected by opinion leaders who are affected by mass media instead of being directly affected by mass media (Littlejohn, 2017). Twitter is opinion leaders talking about and sharing news articles/ research papers, etc. Lots of people only rely on those interpretations instead of going out to directly find information from professionals themselves. My theory is that this would make Twitter advocacy effective.

Baudrillard’s theory of simulation was proposed by Jean Baudrillard in 1981 in France (Littlejohn, 2017). It says that symbols and symbols of symbols are replacing the real thing when people think about things (Littlejohn, 2017). My theory is that if mental health advocacy on Twitter in mental health month is not effective then it is because the tweets are about mental health month and not about mental health.

The effects tradition was proposed by Raymond Bauer in the 1960s (Littlejohn, 2017). It says that mass media doesn’t have as much of an effect on people as scholars have previously thought (Littlejohn, 2017). Does social media messaging about mental health awareness not work because people are not affected by media anymore when they are being bombarded with ads that they try to ignore all day?

Literature review

In recent years mental health acceptance has been on the rise according to many studies. According to Robinson and Henderson (2019) there was significant improvement between 2009 and 2017 in knowledge about mental health, attitudes toward mentally ill people and desired social distance from people with mental illness. Schomerus et al. (2012) also found that there was greater mental health literacy and better acceptance of seeking professional help than before. Rhydderch et al. (2016) also found that there have been significantly more articles published about destigmatizing mental illness in 2014 than in 2008. Poreddi, Thimmaiah & Math (2015) talk about how even medical students tend to have negative opinions about people with mental illness. This means that these trends towards a more accepting public and less stigma around mental health could impact more than just mentally ill people’s personal relationships. The stigma could even keep them from getting adequate health care services. But there is still a long way to go to entirely get rid of stigma around mental illness. For example, Walkden, Rogerson & Kola-Palmer (2021) found that the public still desires social distance from offenders with mental illnesses. Both Alsubaie et al. (2020) and Abi Doumit (2019) found that people who have been exposed to mentally ill people are more likely to have positive attitudes towards mental health. This shows that mental health advocacy on platforms like Twitter, where anyone can share their first hand experiences with mental illness and where people can feel a personal connection to these people, is very important.

There have been many studies on the effectiveness of mental health advocacy in general. Stonski et al. (2017) found that mental health advocates play a very important role, since many mentally ill people are marginalized, so they need people to fight for their rights. Morisson et al. (2018) also found that mental health advocates play an important role, since mentally ill people can contact them to help them achieve successful communication with mental health professionals. The study also found that this is a service that mentally ill people often need. They also found that these interactions generally achieved the mentally ill person’s desired outcome (Morrison et al. 2018). Ma and Nan (2018) also found that personal narratives helped promote mental health acceptance, which means that the form of advocacy that the Twitter platform provides could prove even more effective than these traditional mental health advocacy efforts.

Twitter and other social media apps in today’s world are being used for many mental health related conversations. According to Mishra and Triaphty (2019) Twitter can be used successfully to raise awareness about mental health related issues. Robinson et al. (2019) also talks about how Twitter is being used for conversations about mental illnesses. Smith-Frigerio (2020) found that even mental health organizations are using social media to raise awareness and fight stigma. Zhao et al. (2020) found that Twitter is also a good platform for the mental health advocacy of gender and sexual minorities, since they are a twicely marginalized group. Francis (2021) similarly found that it can be helpful for mental health advocacy for black men too for similar reasons. Parrott et al. (2020) and Hoffner (2020) both found that these social media sites can also be a place for people to engage with the mental health advocacy of famous people.

Findings

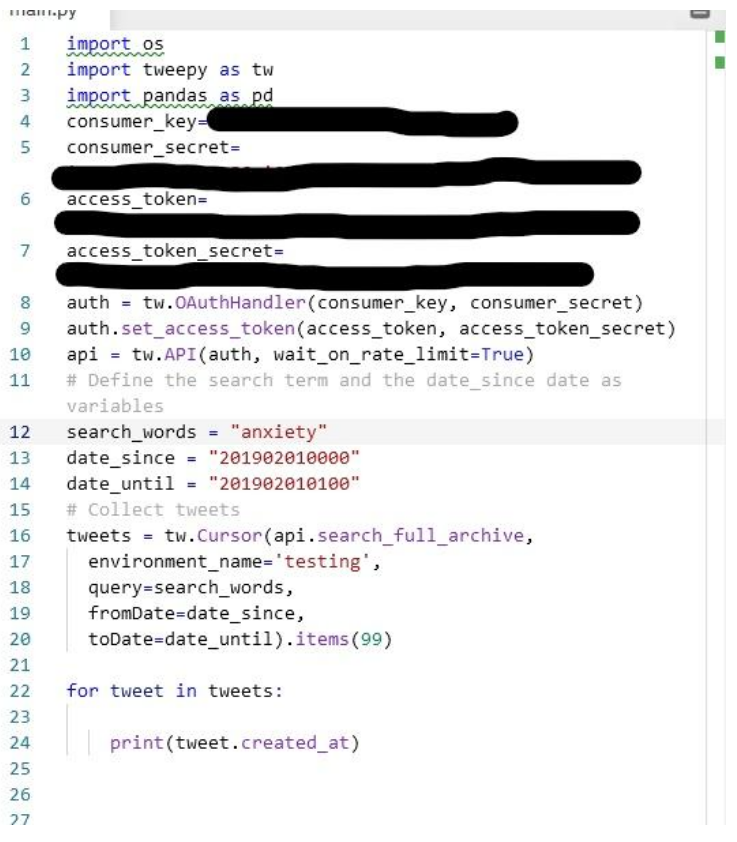

I used the following python code to search Twitter

The above code is just one example, some of the variables- like the time range or the search word- had to be changed with every search. The variables called “consumer_key”, “consumer_secret”, “access_token” and “access_token_secret” are blacked out because those were provided to me with my Twitter API access and I am not allowed to share them with other people.

In the code, I first had to import the corresponding python libraries that I needed to access, then I provided the keys that identified me and gave me access to search Twitter. After this I needed to define the variables for the search term and the date range. Once that was established I could start collecting tweets by calling up all the tweets corresponding to my variables from the full Twitter archive. After this I needed to print the exact time and date of the tweets so I could analyze their frequency.

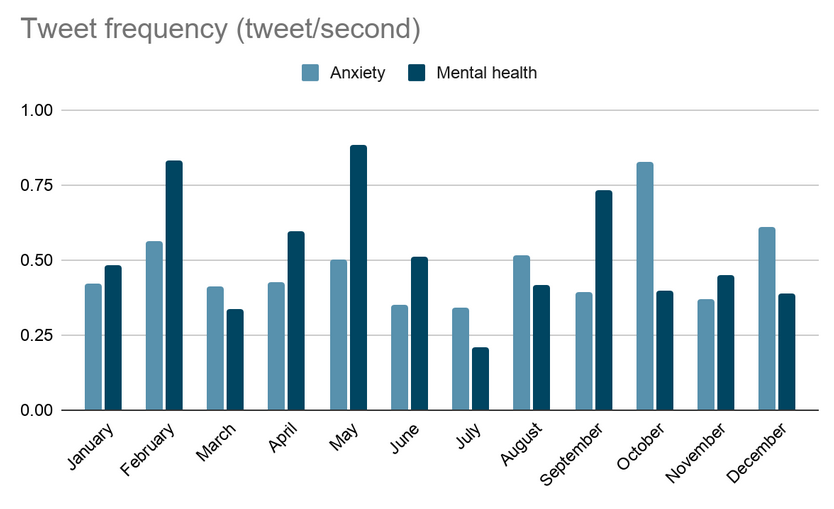

The search on Twitter API turned up the following results:

The above chart shows the amount of tweets using the phrases “anxiety” and “mental health” per second on the dates mentioned in the method section. Looking at the anxiety graph, the month of May is above average, but doesn’t immediately stand out. This could be because there are many other awareness days/weeks/months and other life events that prompt people to talk about their anxiety more than average. On the other hand, on the mental health graph, May is clearly the month where people most frequently use the phrase. Based on this small dataset, the answer is inconclusive, but it does suggest that people’s use of mental health related words increases in May.

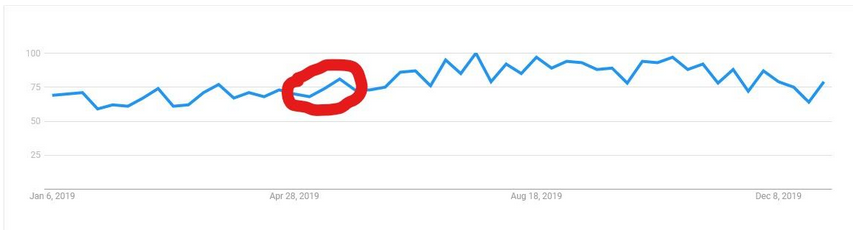

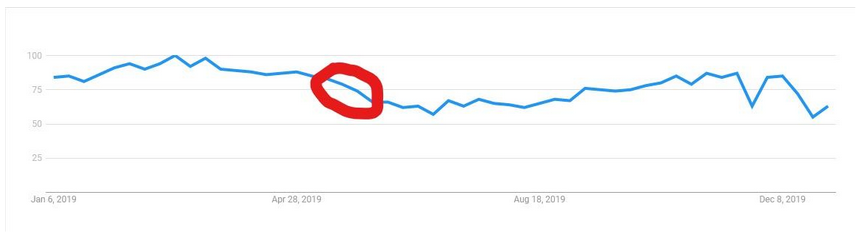

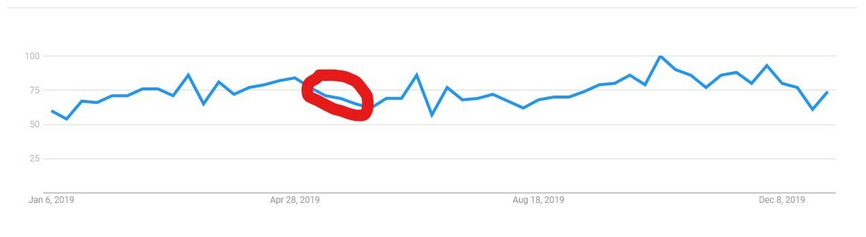

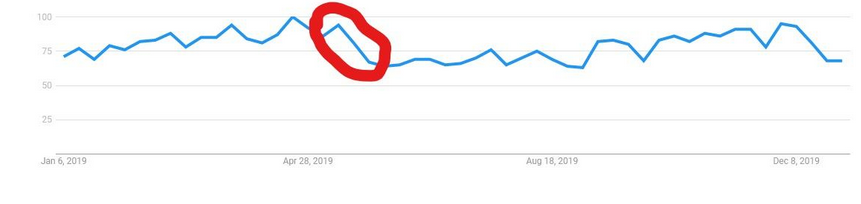

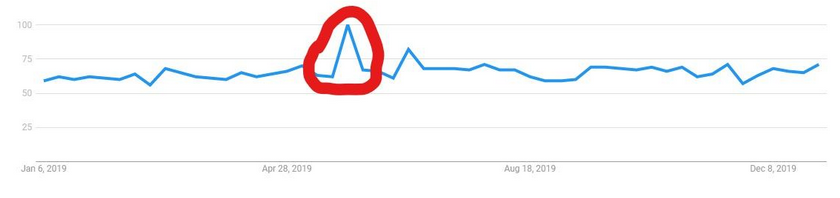

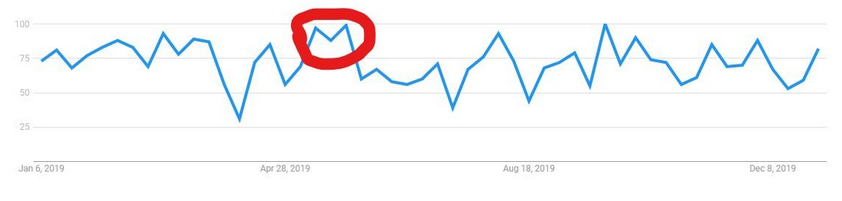

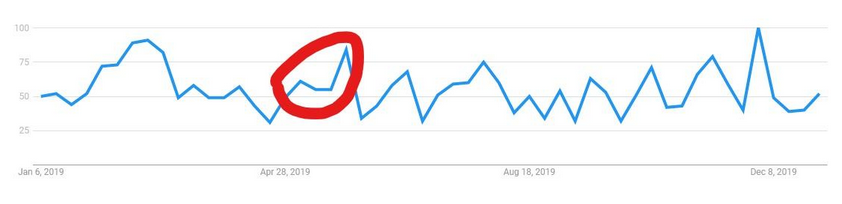

The search on Google Trends turned up the following results:

“Therapist near me”:

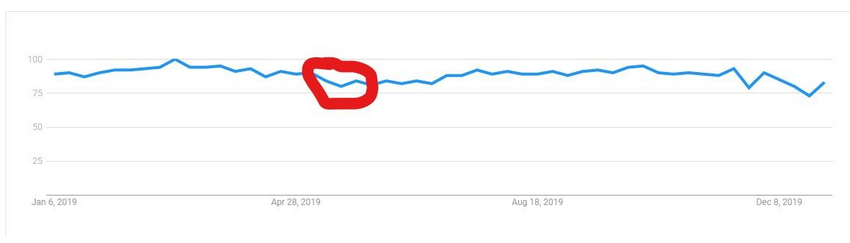

“Anxiety”:

“Depression”:

“Bipolar Disorder”:

“Schizophrenia”:

“Dementia”:

“Do I have anxiety?”:

“Do I have depression?”:

“Do I have bipolar disorder?”:

“Do I have schizophrenia?”:

“Do I have dementia?”:

The line charts represent interest over time so they range from 0 to 100 based on the interest in the word/phrase compared to the highest point on the chart. The approximate location of the month of May is circled in red on all of the charts, although for my analysis I looked at the specific dates detailed in my method section for my analysis, highlighting the month of May is just to get a clearer visual demonstration of the data. Some of the data—including “Do I have dementia?”, “Do I have schizophrenia?” and “Do I have bipolar disorder?”—are noisy, so I disregarded those when looking at the data. The rest of the data doesn’t conclusively show that people search for these terms indicating mental health seeking behaviour more in the month of May than they do the rest of the year, even though some of them do show a slight increase.

Comparing these two things, we can see that there doesn’t seem to be a correlation between the increase in the number of mental health related tweets in Mental Health Awareness Month and people searching for mental health services and advice. This could suggest that the mental health advocacy happening on Twitter is not very effective at getting people to take action on bettering their mental health.

If we apply the aforementioned theories to my findings, we can immediately see that the effects tradition theory seems to apply to these findings the most easily. People’s Google searches about mental health seeking do seem to be affected by lots of things, since the charts have lots of ups and downs, but Twitter advocacy does not immediately seem like one of these affecting factors. This confirms the effects tradition theory, which states that people these days are bombarded with too many messages on social media and otherwise easily swayed from their previous beliefs by social media advocacy.

My findings seem to entirely contradict Lazarsfeld’s Two-Step-Hypothesis since the opinion leaders of Twitter did not actually seem to affect the behaviors of people. On the other hand, just because it does not confirm the theory, it also might not entirely contradict it, since people might be even less affected by professionals than they are by Twitter advocates in their mental health seeking behaviors.

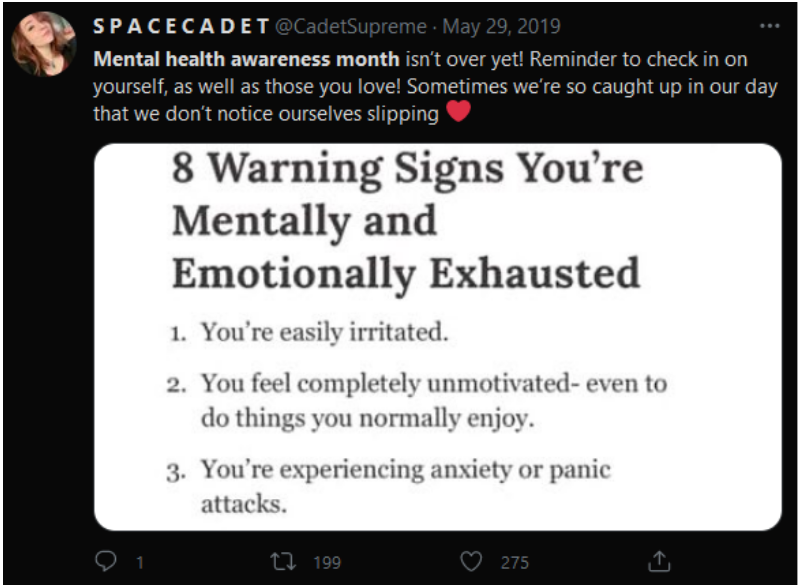

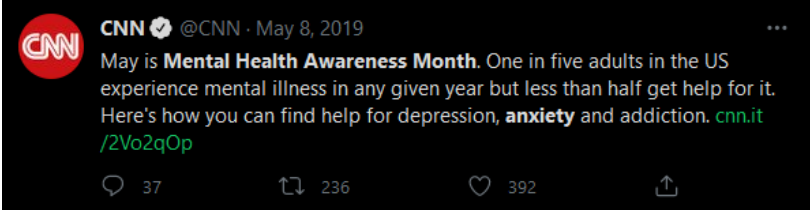

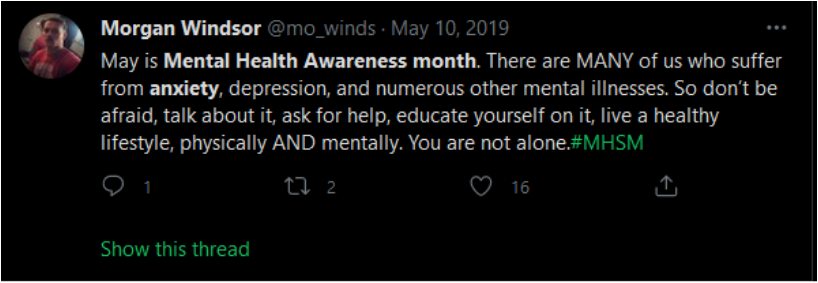

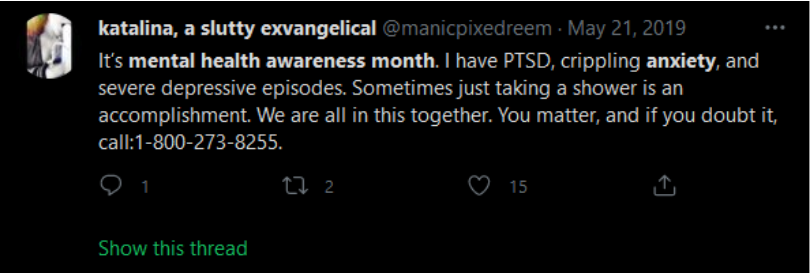

In order to assess if Baudrillard’s theory of simulation has anything to do with why my results are the way they are, I needed to look at the text of some of the actual tweets. Here are some examples of Tweets that I analyzed:

Looking at these tweets, it is clear that just like the tweets that were written in other months, the tweets in May are actually about mental health and raising awareness instead of being only about Mental Health Awareness Month, so Baudrillard’s theory of simulation doesn’t explain why I got the results that I did.

Limitations

The biggest limitation of this study was the restricted access to Twitter data. In the future, this study could be redone with the full dataset that I outlined in my research method section to get more accurate results.

Another limitation of this study is the limited search terms and Twitter words that I analyzed. The research could be done on a wider range of words related to Mental Health Awareness Month to get more accurate results.

Another limitation of this research is that I only looked at social media data from Twitter and internet search data from Google, even though people use different social media sites and search engines too, like Instagram and Bing. The research could be redone on a wider range of social media sites and search engines to get more data.

Another limitation of the study is that it doesn’t consider the intention of the people writing the tweets or searching on Google aside from the few Tweets that I looked at to see if Baudrillard’s theory of simulation applied to my research. This limitation is very hard to overcome because no matter how big a research team is it would be incredibly difficult to find all the people who wrote tweets and searched on Google and interview them about their intentions. On a lower level, researchers could at least look at all the tweets themselves and determine which of the tweets are actually relevant to the research question and exclude all the ones that aren’t.

Another possible limitation of this study is that I did not exclude retweets. I decided to include them because they are still getting the mental health related message to more people, but they could easily be excluded, since they are not adding anything of their own to the conversation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, my research shows that there is no correlation between the amount of tweets about mental health in the month of May and people looking for mental health services and information online. This means that maybe mental health advocates should find a more effective method of getting their message about mental health out to people. But my findings could also mean that the main agenda of mental health advocacy on Twitter isn’t to encourage people to get help and information, but just to tell personal stories or raise awareness. In that case, the lack of an upward trend in Google searches could still be surprising since many people realize that they are dealing with a mental illness based on personal accounts or get the motivation to reach out for help based on more awareness of what a specific mental illness actually looks like.

References

Abi Doumit, C., Haddad, C., Sacre, H., Salameh, P., Akel, M., Obeid, S., Akiki, M., Mattar, E., Hilal, N., Hallit, S., & Soufia, M. (2019). Knowledge, attitude and behaviors towards patients with mental illness: Results from a national Lebanese study. PLoS ONE, 14(9), 1–16. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222172

Alsubaie, S., Almathami, M., Alkhalaf, H., Aboulyazid, A., & Abuhegazy, H. (2020). A Survey on Public Attitudes Toward Mental Illness and Mental Health Services Among Four Cities in Saudi Arabia. Neuropsychiatric Disease & Treatment, 16, 2467–2477. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.2147/NDT.S265872

DuBois-Maahs, J. (2018). The top five most common mental illnesses. The Talkspace Voice. https://www.talkspace.com/blog/the-top-five-most-common-mental-illnesses/

Francis, D. B. (2021). “Twitter is Really Therapeutic at Times”: Examination of Black Men’s Twitter Conversations Following Hip-Hop Artist Kid Cudi’s Depression Disclosure. Health Communication, 36(4), 448–456. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1700436

Hoffner, C. A. (2020). Sharing on Social Network Sites following Carrie Fisher’s Death: Responses to Her Mental Health Advocacy. Health Communication, 35(12), 1475–1486. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1652383

Littlejohn, S. W., Foss, K. A., & Oetzel, J. G. (2017). Theories of Human Communication.

Ma, Z., & Nan, X. (2018). Role of narratives in promoting mental illnesses acceptance. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 26(3), 196–209. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.1080/15456870.2018.1471925

Mishra, D. K., & Triapthy, N. K. (2019). Use of Twitter Application as an Emerging Tool for Creating Awareness and Advocacy for Public Health Diseases: a Study on Mental Health Issues in India. ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry, 20(1), 1-6. http://proxymu.wrlc.org/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=138765341&site=ehost-live

Morrison, P., Stomski, N. J., Whitely, M., & Brennan, P. (2018). Understanding advocacy practice in mental health: a multidimensional scalogram analysis of case records. Journal of Mental Health, 27(2), 127-134. 10.1080/09638237.2017.1322183

Parrott, S., Billings, A. C., Hakim, S. D., & Gentile, P. (2020). From #endthestigma to #realman: Stigma-Challenging Social Media Responses to NBA Players’ Mental Health Disclosures. Communication Reports, 33(3), 148–160. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.1080/08934215.2020.1811365

Poreddi, V., Thimmaiah, R., & Math, S. B. (2015). Attitudes toward people with mental illness among medical students. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 6(3), 349–354. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.4103/0976-3147.154564

Rhydderch, D., Krooupa, A. ‐M., Shefer, G., Goulden, R., Williams, P., Thornicroft, A., Rose, D., Thornicroft, G., & Henderson, C. (2016). Changes in newspaper coverage of mental illness from 2008 to 2014 in England. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 134, 45–52. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.1111/acps.12606

Robinson, E. J., & Henderson, C. (2019). Public knowledge, attitudes, social distance and reporting contact with people with mental illness 2009–2017. Psychological Medicine, 49(16), 2717–2726. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.1017/S0033291718003677

Robinson, P., Turk, D., Jilka, S., & Cella, M. (2019). Measuring attitudes towards mental health using social media: investigating stigma and trivialisation. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(1), 51-58. 10.1007/s00127-018-1571-5

Sasso, M. P., Giovanetti, A. K., Schied, A. L., Burke, H. H., & Haeffel, G. J. (2019). #Sad: Twitter Content Predicts Changes in Cognitive Vulnerability and Depressive Symptoms. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 43(4), 657-665. 10.1007/s10608-019-10001-6

Schomerus, G., Schwahn, C., Holzinger, A., Corrigan, P. W., Grabe, H. J., Carta, M. G., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2012). Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 125(6), 440–452. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01826.x

Smith-Frigerio, S. (2020). Grassroots Mental Health Groups’ Use of Advocacy Strategies in Social Media Messaging. Qualitative Health Research, 30(14), 2205-2216. 10.1177/1049732320951532

Stomski, N., Morrison, P., Whitely, M., & Brennan, P. (2017). Advocacy processes in mental health: a qualitative study. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14(2), 200-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2017.1282567

Walkden, S. M., Rogerson, M., & Kola-Palmer, D. (2021). Public Attitudes Towards Offenders with Mental Illness Scale (PATOMI): Establishing a Valid Tool to Measure Public Perceptions. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(2), 349–356. https://doi-org.proxymu.wrlc.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00653-0

Zhao, Y., Guo, Y., He, X., Wu, Y., Yang, X., Prosperi, M., Jin, Y., & Bian, J. (2020). Assessing mental health signals among sexual and gender minorities using Twitter data. Health Informatics Journal, 26(2), 765-786. 10.1177/1460458219839621